When I listen to music, when I consume any kind of media, really, there are two primary components from which I derive value. Those are, you guessed it, pleasure and interest. If something- a movie, a painting, a novel, a song, is “good”, it means that that thing is pleasant and/or interesting. If something is pleasant, it means the act of it and its associations are enjoyable to experience in and of themselves. If it’s interesting, it promotes thought and curiosity. That which is pleasant is that which is familiar, intuitive, comfortable, and safe. That which is interesting is that which invokes curiosity and is new, unknown, and foreign. We enjoy pleasant because we enjoy familiarity, we enjoy reigning over our domain. We enjoy interesting because we enjoy curiosity, we enjoy conquest and the expansion of our domain.

That’s the core of this post, that pair of definitions, those concepts, but there is one more thing I need to address and define before I can start properly pontificating. Might feel a little tangential but it’ll make sense in a bit, so bear with me.

I have always believed that anything can become beloved with enough time and repetition. A small part of this is nostalgia, yes, but it’s also just a natural consequence of becoming more familiar with something. As you learn more about something, you discover what’s good about it, what is valuable, what is worth experiencing it again for. I suppose I may need to qualify this somehow: not everything gets better with repetition. I could listen to nails on a chalkboard for a year and, as a consequence of becoming familiar and truly discovering it, learn that I really hate the sound of nails on a chalkboard. But at the same time, I think it’s totally possible that I could instead become a connoisseur. By the end of a year I might be able to point out to you the different sounds a pinky nail makes compared to a thumb nail, and how the thumb is obviously way more satisfying. So maybe the qualification has less to do with the experience itself and more to do with the recipient of that experience. Anything approached in good faith can become beloved with enough time and repetition.

That is to say, any song will grow on you. But if any song will grow on you, the primary criterion for a song’s value isn’t how much you like it, it’s how quickly you will learn to like it. Quality isn’t a static value, it’s the speed at which a dynamic, relative value increases. Anything can grow on you. Call it the Experiential Mold Principle, I dunno.

Why is this? What causes the Experiential Mold Principle? I think it’s just a natural effect of learning, of specializing, of increasing depth and granularity. The human brain is incredibly effective, incredibly curious. When we get enough repetition of an experience, we learn that experience more completely. Things we filtered out the first time are remembered the second. Things we ignored the 13th time are all we notice the 14th. Which matters, because our brains like learning. More than that, we like having learned. We like being and feeling knowledgable and in control, we like the familiar. People who don’t listen to a genre always say that everything in that genre sounds the same, and people who like the genre either say it does but they kinda like it that way (the sameness is safe and comfortable), or they say it totally doesn’t (they have practiced listening to that music and have moved on to hearing more specific, granular parts of the music). At least, that’s my theory. Frankly, all of this is conjecture, and immaterial besides. The reason the phenomenon I’ve observed occurs is irrelevant to my current purposes. What’s important is that it does occur and I have observed it and described it.

Okay, phew. Remaining are my observations on how these concepts work, how they interact with each other, how they interact with the songs they describe, as well as some more overtly subjective commentary regarding my preferences and whatnot. I’ll start with how my primary concepts, pleasure and interest, interact with the Experiential Mold Principle.

We naturally like that which is pleasant because it’s familiar and it is our nature to enjoy the familiar. It’s safe. We like that which is interesting because it means an expansion in our domain. It indulges our curiosity, it is conquest and growth. Interesting things don’t get the immediate familiarity surge we crave; pleasant songs do. But those pleasant songs also don’t grow on us as fast as the interesting ones. So, when I say “pleasant” and “interesting” within the context and understanding of the Experiential Mold Principle, what I’m really doing is describing the growth path of the song: when the song is growing on me the fastest, the slowest, and how fast and slow that is. A “pleasant” song is one that probably has higher baseline enjoyment. Worst case I’m bored, but not displeased. An “interesting” song might have a worse baseline, but as I continue to listen I discover more things I like about it more quickly. That is, that which is pleasant is that which is less quickly affected by the Experiential Mold Principle, that which is slower to grow on you- but often easier to approach in good faith. That which is interesting is that which is more quickly affected by the Experiential Mold Principle, but which may be harder to approach in good faith.

However, that delineation isn’t perfect, far from it. Most obviously because pleasure and interest aren’t two flip sides of a coin, or even opposing ends of a spectrum. They are two different (though deeply connected) concepts with a complex, intertwining relationship. Sometimes that which is “pleasant” is in fact so boring that it’s not at all “easy to approach in good faith”. Sometimes you hear something downright weird and can’t help but listen to it again and again until you outright love it. Pleasure and interest are words I’m using to describe and categorize perception and personal judgement. They bend and warp around themselves and each other, they are malleable and slippery and intricate, because so are we. My simplification of how they interact with the Experiential Mold Principle is useful, but it can only ever be a simplification. There will always be complications and exceptions.

For example.

There is a point at which something is so pleasant that it is also interesting. Pleasant is typically intuitive or formulaic, and so it gets boring relatively quickly. It is expectable, it is something you know and understand, that’s part of how I defined it. Of course something I know and understand and expect will get boring quickly. Except, sometimes it doesn’t. That’s bizarre, fascinating. Why do I not get tired of Jack Johnson? Why does Jim Croce only grow on me? Their music is often simple, uncomplicated, easy to grasp and understand quickly. There are few distinct elements that make me truly curious. But it’s so nice to listen to. Why? Are there distinct elements that I’m not yet able to recognize, or is it something else? Is it something that’s purely personal preference, or is it somehow observable and learnable? I don’t know, and that’s fascinating, intriguing, curious. I don’t know, and that’s interesting. And so, that which is pleasant to the extreme not only is interesting, it becomes interesting. It is interesting by virtue of how pleasant it is. Wild.

It’s clear, then, that pleasant and interesting aren’t opposites, that it’s not so binary. That said, I do tend to prefer interesting over pleasant. Pleasant is fundamentally rooted in sameness and familiarity, whereas interesting is rooted in differentness and foreignness. I don’t want to default to seeking that which is primarily pleasant, because that would be dull. It would make me a dull listener. What’s the point of my whole exercise of seeking out lots of different artists when my like or dislike for them is based on how much they’re the same? To like only that which is pleasant, that which is easy to like, is… well, for one, I don’t believe in ease for ease’s sake on principle. But more than that, for me personally to take that approach would be hypocritical to the core of my listening process, to the idea that governs this project. I am currently and constantly in the process of gathering tons of data, of accruing variety. To reject that is to reject so much of what has made music valuable and meaningful to me.

Beyond that, I myself am just a naturally curious person, and interesting is just so much more… well, interesting. It’s more complex, it gives more the more you look. It has a value on the fifth listen it didn’t have on the fourth, because the more you look the more you see and the more you see the more there is to enjoy and be curious about. That’s a naturally enjoyable process for me. I want to explore and learn and grow and become more than I am. I am constantly in the process of trying to make myself more interesting. How could I dare choose pleasant over interesting? To be clear, I in no way mean to dis on those who do prefer pleasant music. That doesn’t mean that that person isn’t interesting, it just means that they use music as a rest from growth rather than as an opportunity for growth. That’s valid. Some people like to reread the same books. Some people take the same walk every day. I think it could be argued that preferring to keep something pleasant in such a way makes it a form of relaxation and meditation, and that that is not only enjoyable but necessary to continuing a meaningful path of growth- but that’s not what music is for me. Music isn’t something in which I rest, music is something I conquer. That’s what I’ve come to love about it.

I think by now I’ve clearly defined and demonstrated my words, how they affect each other, and how that in turn affects the music they describe. Pleasant is familiar, taking joy from what you already have and know. Interesting is new, finding joy in exploring curiosity and expanding what you have and know. The Experiential Mold Principle helps show how pleasant and interesting interact with music over time. I think having these concepts with specific words is a really valuable tool- I know it has been useful for me so far, and I know that making definitions and terms explicit makes it easier to develop and communicate my thoughts and feelings in general, so I hope these words will continue to be useful in my future listening and music adventures.

Also, a small note: I like these words I’ve identified, I think they fit very well- but there is some awkwardness, particularly with “pleasant”. I think it’s the perfect word for this, but its base, “pleasure”, I think sometimes comes with connotations that do not match how I’m using “pleasant”. “Pleasure” (and especially “pleasurable”) are typically more physical, more sensual, while when I say “pleasant” I just want it to be… nice. You know? I like my choice of words despite that, but does lead to phrases like “Pleasant is”. Maybe that actually just serves to let it be distinct as a term defined by me, though, so who knows really. But yeah, that’s why I’ve written this the way I have.

as demonstrated by

A short preface: the examples I provide here are going to display what I believe to be pleasant and interesting. It will reflect what is familiar and unfamiliar to me, it’s by no means objective. That is inevitable. That said, I still believe pleasant and interesting are useful terms, useful frames through which one can better understand and critique. My hope is that my examples below will provide an example of what pleasant could mean and what interesting could mean, and that that specific definition will provide a range and make clearer what I mean by pleasant and interesting generally. I don’t mean to say that this is pleasant and that is interesting and everything else is wrong. It is plausible, reasonable even, that what I say is so pleasant is interesting you say is pleasant to the point of disregarding interesting, or that what I say is weird you say is unpleasant and vice versa, or whatever the incongruence may be. These words are tools, and this is how I use them.

(And, of course, these examples are few- this analysis can be applied to all artists.)

Jim Croce is probably my favorite example of when pleasant becomes interesting. It is relatively rare for me to hear something simple and pleasant and just fall in love with it, listen to it again and again not knowing just why I love it. Jim Croce hits that mark pretty hard, pretty consistently.

Vampire Weekend is great, a very effective band. I think they’re worth noting here because they’re a pretty solid mix of pleasant and interesting, both within songs and albums- but they also get additional flavor by putting a huge emphasis on garnering interest and complexity from lyrics and theme.

Still Woozy is, I think, one of the most directly effective artists I’ve encountered. I love him and his sound and his whole vibe, he’s just got such solid fundamentals. He is my favorite example of an initial hook, initial pleasant, that gets you in the door to find interesting things later. Pleasant leads into interesting.

Sometimes what is incredibly interesting is patently unpleasant. Because that unpleasantness is a decision, and doesn’t that make you think? AJR I think is my best example of that- they have effects and noises that I actively dislike, but it does makes me pay attention. Not necessarily right or wrong, but certainly high risk.

Beck is a good example of how intense interesting creates a steep learning curve, for good and ill. Beck is often interesting by being just so weird. Not bad, just foreign and bizarre. This model, of being maybe too interesting, is high risk. I typically don’t prefer the risky, but this particular strategy I tend to have a soft spot for.

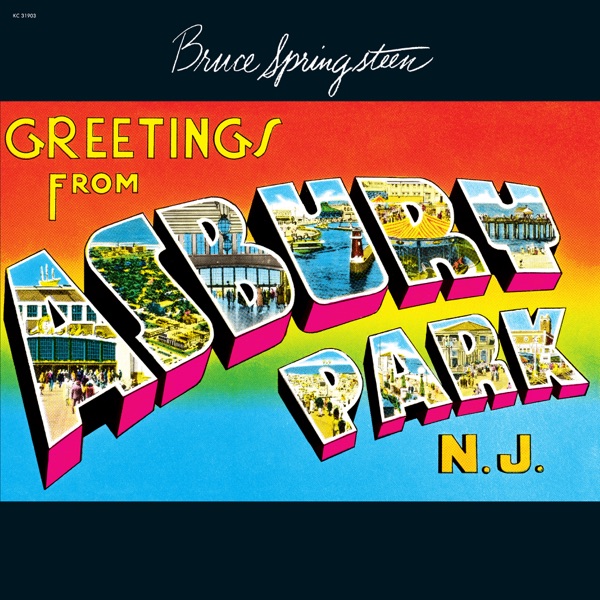

Bruce Springsteen is really, really consistent, to the point that I would just call him repetitive. His repetition isn’t bad, but it is clearly risky. Some people love him, others think he’s just boring. Any time you disregard a value in favor of another value you’re taking a risk. Springsteen is pleasant to the point of disregarding interesting, and that’s risky.